During WWII, the United States’ 14.5 million workers rose to the challenge and answered President Roosevelt’s call to build the “arsenal of democracy.” Workers supported the country and pledged to stop strikes and walkouts during the war, which they did with few exceptions.

Price controls had been in effect during the war and, to a great extent, unions voluntarily accepted stagnant wages to support the war effort. But after the war, Boilermakers and all wage workers had a new enemy—inflation. Goods that had been unavailable or rationed during the war were again available but at high cost with prices rapidly rising. Prices for a variety of goods rose 18% in 1946 alone. Food costs skyrocketed 34%.

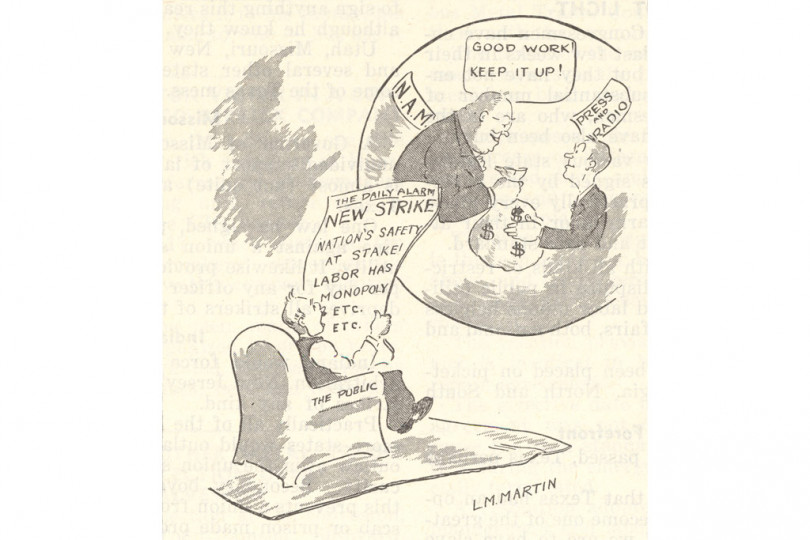

Workers simply couldn’t afford their lives unless their wages increased to catch up with inflation. So, when negotiations failed, they went on strike. In 1946, more workdays were lost to work stoppages than in the six years that came before, as workers used their power to demand wage increases. And Congress, with its ally the National Association of Manufacturers, fumed at worker strikes and slowdowns.

People were clamoring for more goods at the same time union members were striking for better conditions, setting up negative public perception of worker strikes. Media-fueled frenzy over communism infiltrating unions also drove anti-union sentiment. This opened the door for greedy business owners and their friends, the anti-union Republicans who dominated Congress, to make laws to weaken unions.

While several bills were under consideration to limit worker power, the worst of the lot passed Congress and became law: the Taft-Hartley Act. There were many terrible parts of this act that still hurt unions today, with one of the most egregious outlawing the “closed shop.” This opened the door for right-to-work laws (more aptly described as right-to-work for less) that allowed nonunion workers to benefit from union contracts and protections without joining the union or paying dues.

But that wasn’t the only aspect of this hit job against unions. Taft-Hartley separated workers into classes by excluding supervisors and independent contractors. It also permitted employers to petition for a union certification election, undermining the ability of workers and unions to control the timing of an election. Taft-Hartley also established the right of management to campaign against union organizing drives—paving the way for what we see today with captive audience meetings and other nefarious tactics businesses use to cripple union drives for recognition.

Anti-union powers in the U.S. were successful in slowly eroding union power as union density among workers dropped from 35% in the 1940s-50s to 10% today. The good news is that workers have massive power when they band together for collective action. The U.S. has seen increased organizing across many industries, especially since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. With a renewed understanding of the power of solidarity, the time is ripe for growth in the union movement.