The Boilermaker Reporter is an evolution of the first official publication of the “Boiler Makers and Iron Ship Builders of America” first published twice monthly beginning in 1896 named The Journal. Grand President Lee Johnson became the first editor of the new Brotherhood’s first publication.

Johnson focused on producing a journal of practical information that would help Boilermakers and their families. Because postage was costly, The Journal became a catch-all for information of all varieties: monthly reports from the president and the secretary-treasurer, political issues of the day and concerns of the labor movement. It detailed activities of members in each local lodge and offered summaries of working conditions, average hours and wage rates. The Journal even published articles about inventions that could help Boilermakers work smarter.

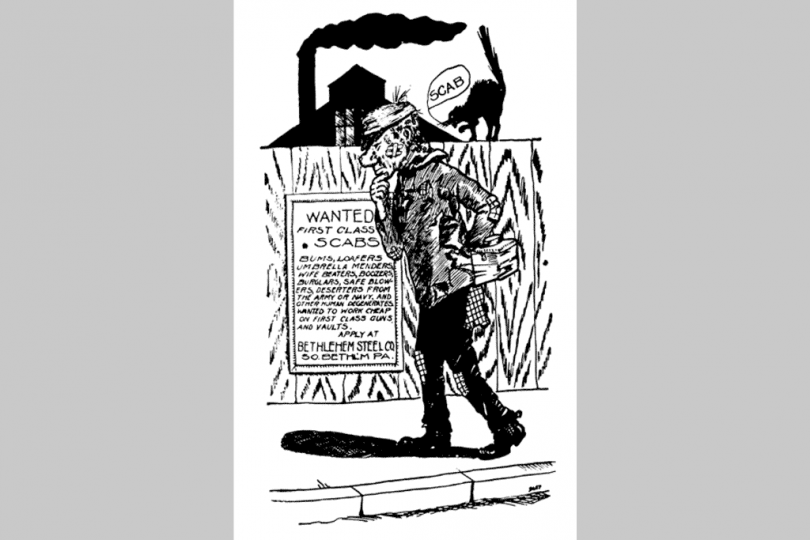

The publication also took up a heated topic in the labor movement, that of the scab. During the early beginnings of the labor movement, around 1810, any worker who refused to join a union earned the label “scab.” How the term came to be is unclear; but in the 1700s, scab was used to describe people of low moral character—which fits with how they were viewed by union members of all the trades.

The definition of a scab evolved over time. By the 1890s, the term scab was widely recognized as being a union tradesman taking nonunion work. It didn’t matter if they crossed a picket line or not. Scabs were reviled in every trade union; so, it’s no surprise that in the early Brotherhood Constitution, any member caught scabbing would be fined $1,000 (a princely sum since at the time Boilermakers were lucky to earn $100 a month).

The vilification of scabs didn’t end with a huge fine. The Journal regularly featured photos of scabs, along with a warning to local lodges to bar them from union jobs. One entry in The Journal reported that a Boilermaker lawyer had successfully defended both the right to picket and the right to call anyone who crossed the picket line a scab. To this day, the use of the term is protected speech. Calling someone who crosses a picket a scab still doesn’t rise to the level of hate speech.

And it wasn’t just unions that hated the scabs. Celebrated author Jack London is credited with giving a colorful description of a scab during a speech in 1903 in Oakland, California. The following has been attributed to London:

“After God had finished the rattlesnake, the toad and the vampire, he had some awful stuff left with which he made a scab. A scab is a two-legged animal with a corkscrew soul, a waterlogged brain and a combination backbone made of jelly and glue. Where other have hearts, he carries a tumor of rotten principles.”

The Journal has evolved, as has the Brotherhood Constitution. But one thing that hasn’t changed: A union worker crossing a picket line is still called a scab.