THE ENVIRONMENTAL Protection Agency may soon increase its estimates of life-cycle greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from natural gas-fueled power generation, according to an article in Pro Publica by Abrahm Lustgarden. Citing an EPA technical support document, Lustgarden points out that the higher estimates would mean that natural gas is only marginally more climate-friendly than coal.

For years, advocates for natural gas have claimed it produces 50 percent less GHG than coal, making it the preferred fossil fuel for power generation. But those estimates are based primarily on what issues from the smokestack. The EPA working paper suggests that when the estimates include the methane and other pollution emitted when gas is extracted and transported to customers, the difference between coal and natural gas is greatly reduced.

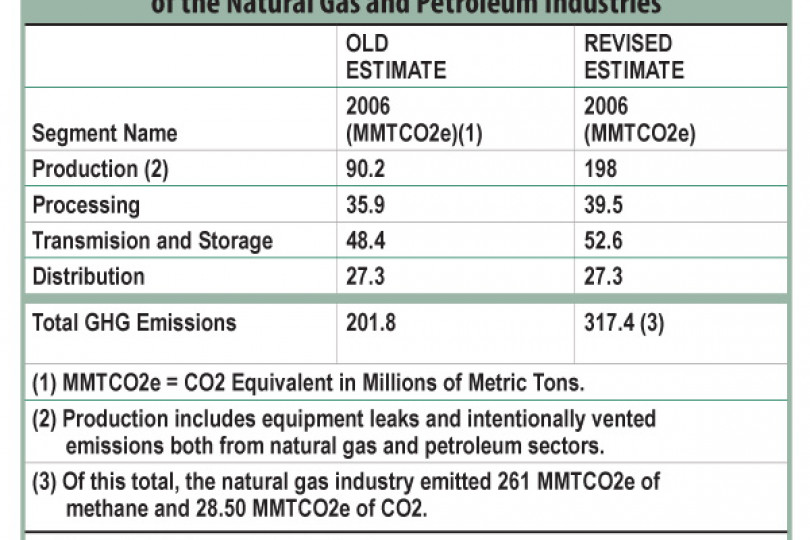

The EPA’s new analysis doubles previous estimates for the amount of methane gas that leaks from loose pipe fittings and is vented from gas wells. Calculations for some gas-field emissions jumped by several hundred percent. Methane levels from the hydraulic fracturing of shale gas were 9,000 times higher than previously reported.

These new calculations suggest natural gas may be as little as 25 percent cleaner than coal, a conclusion reached in 2007 by Paulina Jaramillo, an energy expert and associate professor of engineering and public policy at Carnegie Mellon University. In a paper published in Environmental Science & Technology, she and fellow researchers went so far as to say that a coal plant using carbon capture and storage may actually produce lower GHG emissions than a natural gas plant which must pipe fuel a long distance.

CO2 CH4, and CO2e

WHILE THE NEW studies indicate a much higher release of greenhouse gases as natural gas is extracted and transported, it is especially troubling that methane (CH4) is among those gases. Burning either coal or natural gas produces large quantities of CO2, though natural gas produces less. But methane is a far more potent GHG than CO2. And gas drilling emissions account for an estimated one-fifth of human-caused methane in the atmosphere.

Scientists use the term CO2e (carbon dioxide equivalent) to measure a gas’s global warming strength. EPA calculates methane as being 21 times as potent as CO2, so releasing one ton of methane is equivalent to releasing 21 tons of carbon dioxide. As studies have begun to show more methane is being released than previously thought, the EPA’s estimates of natural gas’s GHG emissions has been revised accordingly.

Even this most recent revision may eventually prove too small, according to Robert Howarth, a professor at Cornell University. He points out that as natural gas becomes more widely used, the United States will draw more of it from shale gas. His research suggests that drilling in shale releases 1.3 to 2.1 times as much methane into the atmosphere as gas taken from conventional sources. Shale gas wells rely heavily on “fracking” — using water to fracture the shale around well bores. Howarth contends that this process allows natural gas and methane to escape.

“Even small leakages of natural gas to the atmosphere have very large consequences,” Howarth wrote in a March 2010 memorandum. “[I]n fact, natural gas may be worse [than coal] in terms of consequences on global warming.”

Findings may impact power producers

AS AMERICA’S POWER producers determine what types of facilities they will build to provide electricity for the future, any questions regarding the viability of an energy source loom large.

In recent years, natural gas has been gaining on coal as the fuel of choice for electrical power generation, despite long-held concerns regarding its price and availability. Since 1997, there have been five natural gas price spikes. As the National Research Council noted in a 2009 report, “[N]atural gas . . . can be one of the lowest cost — or one of the highest cost — sources of electricity.” That same year, the California Energy Commission reported, “Past efforts to forecast natural prices have been highly inaccurate.”

The gas industry continues to promise increases in production of five percent or more a year, but if domestic reserves turn out to be smaller than predicted, many power plants may need to pipe gas from distant locations or purchase liquefied natural gas from overseas. The additional processing and transportation necessary add emissions, increasing the GHG footprint of natural gas so it nearly equals that of coal.

These uncertainties lead Nick Akins, president of American Electric Power, to support developing carbon capture and storage (CCS) technology. If CCS works, coal-based power emissions could drop by 80-90 percent.

For further reference

Abrahm Lustgarten’s article

[www.propublica.org/article/natural-gas-and-coal-pollution-gap-in-doubt]The EPA’s technical support document

[www.propublica.org/documents/item/epa-greenhouse-gas-emissions-reporting-from-the-petroleum-and-natural-gas-iTable 2 from the above document

[www.propublica.org/documents/item/epa-greenhouse-gas-emissions-reporting-from-the-petroleum-and-natural-gas-i#document/p10]Paulina Jaramillo’s article in Environmental Science & Technology

[www.propublica.org/documents/item/comparative-life-cycle-air-emissions-of-coal-domestic-natural-gas-lng-and-s]Robert Howarth’s memorandum

[www.propublica.org/documents/item/cornell-university-3-2010-draft-report-on-greenhouse-gas-emissions-from-hyd]