The establishment of auxiliary locals by the Boilermakers’ union was a product of segregationist practices during the early 20th century. While this isn’t a proud moment for the union, it’s an important part of Boilermaker history that cannot be ignored.

These were Jim Crow-era ideas that marginalized Black workers, subjecting them to discriminatory rules and limited union representation. Auxiliary locals, controlled by nearby white locals, were not allowed to send their own delegates to Convention, which silenced Black members in union decision-making.

Members of auxiliary locals lacked business agents, grievance committees or any channel to negotiate with employers. Black workers also faced barriers to career advancement, such as being excluded from apprenticeship programs and facing restrictions on promotions from helper to mechanic. Union insurance policies were also unequal, with death and injury benefits for Black members set at half the amount granted to white members.

Black members paid the same dues as white members but received less in return. This inequitable treatment was not unique to the Boilermakers, as many unions did the same. Since the practice ended in the last century, the union has apologized for its past treatment of Black members and changed its ways.

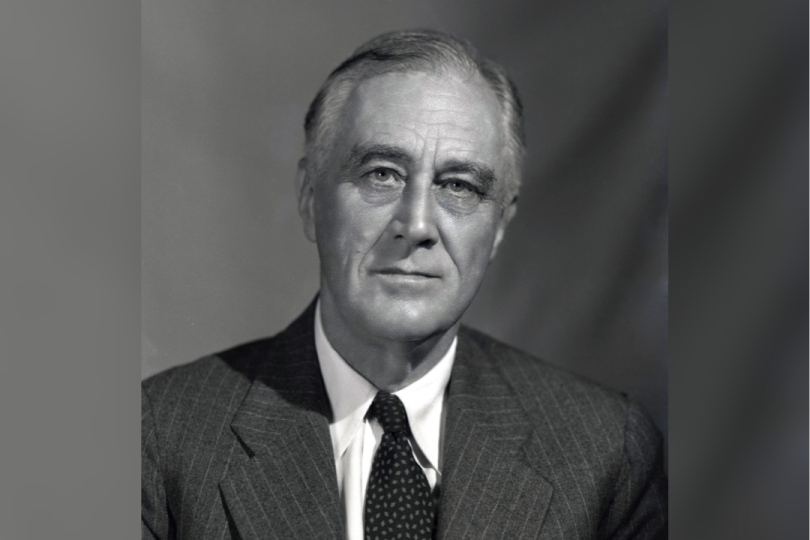

The situation began to shift with the onset of World War II. Although segregation was still widespread, the federal government started to challenge racial discrimination in wartime industries. President Franklin D. Roosevelt barred companies that held federal contracts from engaging in racial discrimination, leading to the establishment of the Fair Employment Practices Committee in 1941. The FEPC encouraged workers to report discriminatory practices—especially workers employed by companies tied to federal defense contracts.

By late 1942, complaints began surfacing from Black Boilermakers in Portland, Oregon. Local 72 had 65% of shipyard employees in the region, including those at the massive Kaiser Shipyards. Eager to diversify its workforce, Kaiser began recruiting Black workers from New York City, but Local 72 resisted integration. They formed an auxiliary local for Black members. Local NAACP leaders even backed the decision because they saw it as a step toward inclusion.

However, many Black workers were unwilling to accept a segregated system. In July 1943, more than 300 Black workers at Kaiser Shipyards were dismissed for refusing to join the auxiliary local, citing inequities. The firings sparked FEPC public hearings, where Local 72’s attorney, Leland Tanner, defended the auxiliary system by claiming, “We live in that house, we didn’t build it and we’re not the architects of it.” Tanner’s statement highlighted the nature of segregation in American society, where legal precedents, such as the Supreme Court's Plessy v. Ferguson decision in 1896, had enshrined racial separation as an acceptable norm.

Segregation reached a boiling point when Providence, Rhode Island, Local 308 integrated its lodge by accepting around 500 Black members. In 1943, the local elected a Black delegate for Convention. Union leadership was not pleased.

IVP William J. Buckley intervened, stating the Black delegate would not be recognized and his vote would be invalidated. Subsequently, he pressured Local 308 to create a segregated auxiliary lodge.

It wasn’t the hoped-for outcome, but the controversy surrounding the auxiliary system exposed the racial divides within the union, which mirrored the broader national struggle over civil rights. And future battles would eventually dismantle segregated practices in the Boilermakers.

In the next issue of The Boilermaker Reporter, read how the auxiliary lodge practice ended at the Boilermakers.