Figuring out what the contract actually says is not always easy

Sometimes stewards feel that they need a law degree to do their jobs correctly. That's because the key to success in most grievances lies in being able to interpret what the contract says.

And that can sometimes be very difficult.

You don't need to be a lawyer, though, to interpret your collective bargaining agreement. You just need to learn some of the methods lawyers and arbitrators use to interpret the contract and how it applies to the grievance you are handling.

First, you'll want to see if this subject has come up in other grievances and, if so, how the matter was handled in the past. Generally, the resolution of a prior grievance on the same matter will determine how you'll resolve this grievance.

If the issue hasn't been addressed before, you need to determine whether it is mentioned in the contract, either directly or by reference to another document. If so, your job of interpreting begins.

Does the Contract Mention the Issue Specifically?

If the contract never mentions the issue of your grievance at all, then you obviously have to find some other support for the grievance. If the issue is mentioned, read that section of the contract carefully to see if the issue is specifically mentioned and the language is clear and unambiguous.

For example, look at this language:

"Section 1: Management shall continue to make reasonable provisions for the safety and health of employees."

This language mentions the company's responsibility for safety and health, but leaves a lot of room for interpretation. You might not say it is unclear, but it certainly leaves a lot of room for different interpretations. Key words in this language are "continue to make" and "reasonable provisions."

Let's say that the company decides to stop supplying the work gloves it has supplied in the past. Obviously, they are not "continuing" to make provisions, so that specific word may support a grievance. On the other hand, you would probably not be able to use this section to force the company to begin distributing safety equipment that they have not distributed in the past.

This section also contains a dangerous hedge word: "reasonable." Supplying safety goggles might seem like a "reasonable" provision to you, but the company may be able to successfully argue that it is unreasonable to expect them to provide such personal items.

Let's add another section to that contract.

"Section 2: Wearing apparel to properly protect employees from injury shall be provided by management in accordance with practices now prevailing or as such practices may be improved from time to time."

The language here is much more specific. When one part of a contract is general or vague and another is specific, the more specific part applies. Work gloves would definitely fall under "wearing apparel;" safety goggles might not.

The phrase "in accordance with practices now prevailing" is more specific than "continue to make," while the phrase "or as such practices may be improved" allows the company to change the policy by improving it. If providing the safety goggles was the "prevailing" practice when the contract was signed, the company can only change that policy by doing something better.

Of course, we don't always agree on how a practice "may be improved." If the company can save money by offering cheaper gloves, they'll call that an improvement because it improves their bottom line. What happens if your members don't like the new gloves? Do you have a grievance? How would you argue your case?

Another point to remember is that when the contract mentions one item, but fails to mention another similar item, the contract is usually interpreted to mean that the unmentioned items were intended to be excluded. In the example above, the language mentions "wearing apparel." Would you interpret that to mean work boots? What about safety glasses?

Is The Language Clear And Unambiguous?

Determining whether the contract clearly states what was intended can be very frustrating. In a dispute, each side is inclined to make a clause mean what they want it to mean. When the company interprets a clause to mean one thing and you think it means something else, you need to make an effort to look at the language objectively.

Try to read the clause the way some stranger who knows nothing about the case and has no interest in it would read the language. Essentially, that's what happens when the arbitrator comes in. The arbitrator has nothing to gain or lose, so he or she can be objective.

Look at this language: "Shift workers will be given 20 minutes from their regular shift for eating lunch, at the convenience of the management." It seems pretty clear. But would it apply to people who work only days?

Ambiguous language is the type of unclear language that can be understood two different ways and both readings are reasonable. For example, "Employees must report any absence for illness or injury prior to the beginning of their shift" is ambiguous. The company would no doubt say it means you need to call in every day you will be out, but it is reasonable to read it as meaning you could call in once for a multiple day absence.

An arbitrator will consider several factors when interpreting language that is unclear or ambiguous.

- What was the intent of the parties when they negotiated? Courts have consistently ruled that what the parties believed they were agreeing to overrules a strict reading of the actual language. If you intend to use this factor to interpret the language, you'll need to look back at the bargaining committee's notes, initial demands, how the language differs from previous contracts, and other documents relating to what people were thinking while at the negotiating table.

- Does one interpretation deprive a worker of other contract rights? The arbitrator will disregard any interpretation of the contract that would break a law or violate a worker's civil rights.

- Has either party permitted a certain interpretation over a period of time without protest or appeal? This criterion can work for both the company and the worker. If you let the company get away with using their interpretation of the language for several years before anyone files a grievance, don't expect the arbitrator to take your side.

- What has been the company's past practice in similar situations? What is normal practice in the industry?

- Would one interpretation bring harsh or nonsensical results? Arbitrators opt for resolutions they believe will bring just and reasonable results. For example, if the contract reads, "workers must call in sick every day of an absence for illness or injury," it would be harsh and unreasonable to expect a person in a coma to call in sick every day.

- If two interpretations of the language seem equally reasonable, the arbitrator will probably not assess a penalty

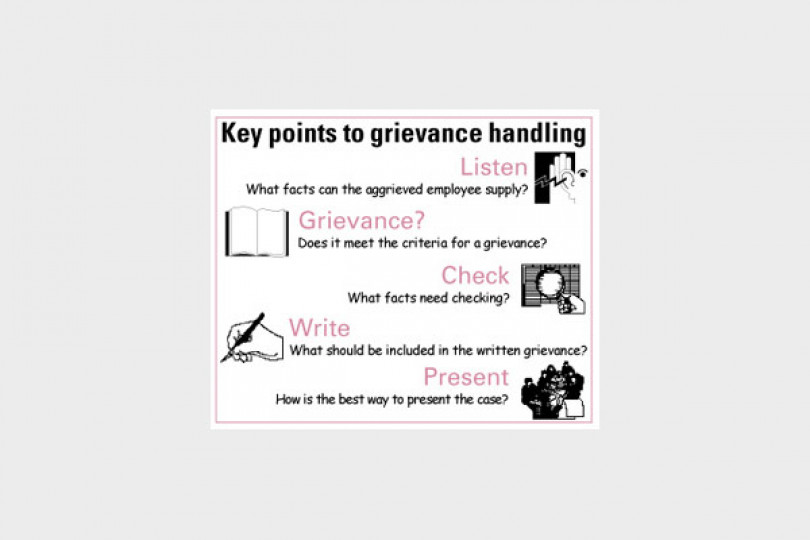

Key Points To Grievance Handling

Listen - What facts can the aggrieved employee supply?

Grievance? - Does it meet the criteria for a grievance?

Check - What facts need checking?

Write - What should be included in the written grievance?

Present - How is the best way to present the case?

Key Words And Phrases In Contracts

Many words and phrases that frequently appear in contracts can cause problems for people when they first begin interpreting contract language. You may use these terms in different ways in your everyday life, but they have very specific meanings when they appear in a contract.

- May -- Implies permission, but not obligation. Something can be done if the party wants to do it, but they are not required to do so. For example, "The company may provide a holiday turkey in December." If you don't get one, you have no grievance.

- Should -- Expresses moral obligation, but not legal obligation. "The company should provide a holiday turkey in December." Again, don't count on getting one.

- Shall -- Denotes compulsion. The party is obligated to act. "The company shall provide each employee a holiday turkey in December." This one you can take home and cook. If you don't get it, you've got a grievance.

- Will -- Simply denotes the future. Does not imply compulsion. This verb confuses a lot of people. If you want to make sure the company does something, use "shall" or "must," not "will."

- Must -- Implies necessity or compulsion. Stronger than shall. "Employees must call in prior to an absence for illness or injury." If you're going to stay out sick, you are obligated to call in first.

- When (or if) appropriate -- Allows full discretion to management. "When appropriate, the company may reassign employees to jobs in a similar pay class." In this case, the company decides where you work. Though you may argue over whether the pay is truly "similar," the company can reassign you whenever they feel it is appropriate.

- When (or if) practical -- Slightly more compelling than "when appropriate." The union can argue whether something is practical. "When practical, employees may take their breaks outside so they can smoke." In this example, there is a great deal of room for arguing either way.

- When (or if) practicable -- Means when "workable." Management decides what is workable, so the decision still belongs to them, but there may be room for discussion.

- When (or if) possible -- Very compelling. The only argument for inaction is that it is not possible to do so -- a very difficult case to support. "When possible, the company will notify employees 14 days prior to any layoff." Could the company argue it was impossible for them to see the layoff coming?

- Normally -- Allows management to decide when a situation is other than normal. Arguments challenging what is "normal" require a great deal of documentation with evidence over a long period of time.

- To the maximum extent practical -- Management decides whether an action is practical, so they determine the limit here.

- To the maximum extent possible -- How much is possible? A lot! You'd better hope this phrase is part of a sentence obligating the company to do something -- and not you.